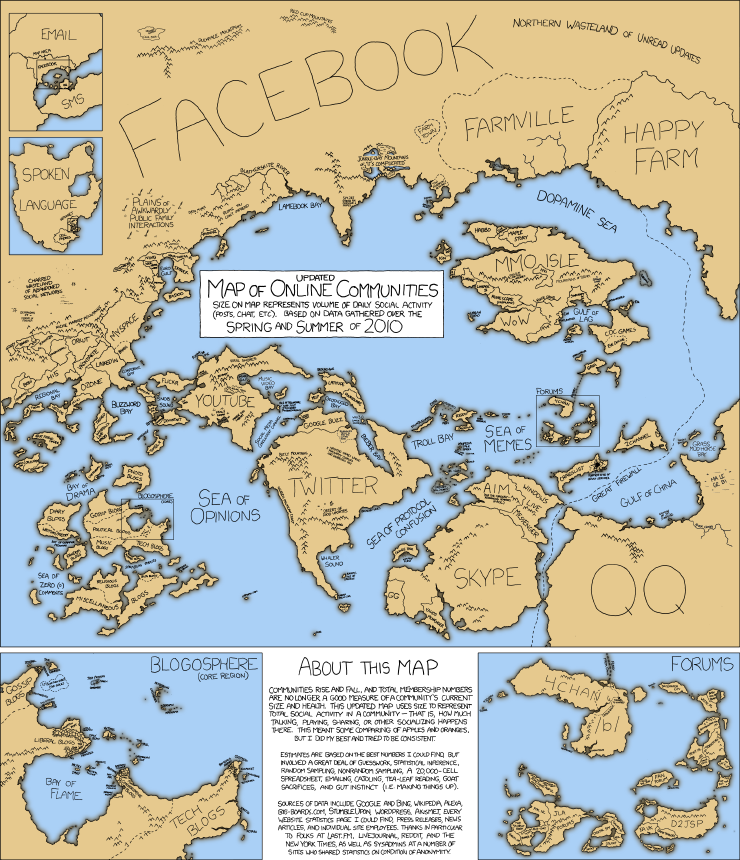

xkcd’s attempts to visualize the territory that is cyberspace:

It would be irresponsible to discuss weaponized animals without covering sharks with laser beams on their heads, so:

On a slightly more serious/relevant note, a friend of mine pointed me to Boston Dynamics’ BigDog project (it’s even made wikipedia):

Pretty wild.

As we dive into the ethics of cloning, it’s impossible not to tip our collective hat to Calvin and Hobbes and the transmogrifier:

Arriving at a rock-solid, comprehensive definition of what is and isn’t science fiction isn’t necessarily something we need to do, let alone in week 1. That said, obviously the question is present for us from the get-go. What counts as science fiction? What kind of a thing is science fiction? How can we recognize it? What about things that look superficially like science fiction but aren’t really? What about things that don’t look like it but are? io9 has a useful roundup of a bunch of different definitions of science fiction, one of which comes from the Darko Suvin book we read a chunk of, and some others we may encounter later in the course. Some of them are great and useful; some are pretty bad. Damon Knight’s is probably the classic, and it may be our lowest common denominator, the only definition we can all agree upon: “Science fiction is what we point to when we say it.” For Ray Bradbury (whom I assume many of you have read), science fiction is “the art of the possible,” as compared to fantasy’s “art of the impossible” (another version of rocket ships and magic carpets). James Gunn’s definition is also worth reading:

“Science fiction is the branch of literature that deals with the effects of change on people in the real world as it can be projected into the past, the future, or to distant places. It often concerns itself with scientific or technological change, and it usually involves matters whose importance is greater than the individual or the community; often civilization or the race itself is in danger.”

To these, I’d like to add a couple others. The first, and longest, is from Frederick Pohl, whom we’ll read later in the semester:

“Does the story tell me something worth knowing, that I had not known before, about the relationship between man and technology? Does it enlighten me on some area of science where I had been in the dark? Does it open a new horizon for my thinking? Does it lead me to think new kinds of thoughts, that I would not otherwise perhaps have thought at all? Does it suggest possibilities about the alternative possible future courses my world can take? Does it illuminate events and trends of today, by showing me where they may lead tomorrow? Does it give me a fresh and objective point of view on my own world and culture, perhaps by letting me see it through the eyes of a different kind of creature entirely, from a planet light-years away? These qualities are not only among those which make science fiction good, they are what make it unique. Be it never so beautifully written, a story is not a good science fiction story unless it rates high in at least some of these aspects. The content of the story is as valid a criterion as the style.”

In his intro to Fast Forward, an SF anthology, Lou Anders suggests, along the same lines as Gunn, that science fiction is “a tool for making sense of a changing world.” In this case, we define science fiction not according to what it contains or what style it embodies, but rather according to the uses to which it is put, the problem or dilemma it exists to confront. In other words, Gunn defines science fiction not according to what it is, but according to what it does, to the conditions it responds to (namely change, and change that’s becoming more rapid and unpredictable).

Robert Charles Wilson distills the essence of SF as “human contingency”: “The world in the past was a very different place than it is now; the world we live in could have been a very different place than it is; and the world will inevitably become a very different place in the future.” These three points are all very true, and they’re all very crucial. Change, yes, but contingency—the notion that the way the world was, is, and will be is not natural and inevitable but contingent, dependent upon tweaks and changes and events and happenings. Part of what science fiction forces us out of is the sense that the way the world is is the only way it possibly could have been; this sense of human contingency is science fiction’s antidote to complacency, inevitability, and a lack of imagination outside of the status quo.

Anders summarizes the Wilson point as follows: “There you have it. Science fiction is skepticism. Science fiction is rationalism. Science fiction is the notion that there are other perspectives out there, other modes of thinking, other ways of being than those in front of your nose, worlds beyond your current understanding. Science fiction opens the mind to the notion of change. Science fiction is enlightenment packaged in narrative.”

* * * * *

Even if we can’t necessarily pin down or agree on which of these definitions we ought to go by, they can at least give us a sense of some of the things that are at stake in science fiction and conversations about science fiction; they can give us lenses through which to understand science fiction and a science fictional world.

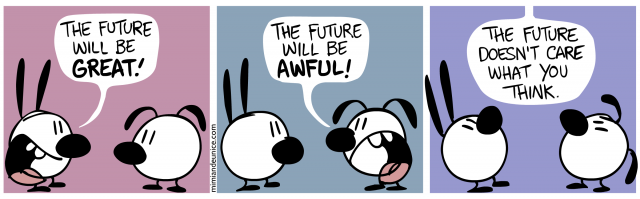

The last line here aptly summarizes, I think, why science fiction is simultaneously so exhilarating and so frightening. On the other hand . . as we’re starting to see, the future kind of does care what you think, in the sense that a techno-utopian attitude would produce a very different future from a dystopian, anti-tech paranoia, and so on. At the very least, the point that the future has autonomy and a life of its own meshes well with “The Gernsback Continuum.”

With “The Gernsback Continuum” and its phantom futures in mind, it’s worth thinking about how other kinds of futures function rhetorically, how they bleed through into the present, how they set the terms for our experience of our own world. For instance, imagine if all stories were written like science fiction stories—imagine what it would be like to see the world through that lens, to experience our existing technologies with the awe and astonishment with which science fiction encourages us to see imagined technologies.

Channeling the Tom Disch excerpt we read, we can also think about versions of the future that have been offered—sold, quite literally sometimes—to us over the years. Some of the things we’ve been tantalized by, in fiction or advertising or both, have yet to come through. Some of them have.

Either way, what I want to establish up front is the extent to which science fiction and science fictional imaginings of the future aren’t escapism, aren’t disconnected from the contemporary world—the ways in which they’re less a matter of making predictions about the future than about making things happen in the here and now. Instead of thinking about science fiction as a category for most or all fiction dealing with a certain set of topics (artificial intelligence, space travel, aliens, time travel, virtual reality), what would it mean to think of science fiction as a mode, an aesthetic, a worldview? Put another way, what would it mean to think of it not as a noun or a set of nouns (science fiction is robots, lasers, spaceships, and little green men), but as a verb? What kind of worldview does it model for us? What does it look like to experience your surroundings and your circumstances through the lens of science fiction? What does it mean to say we’re living in a science fictional universe?