Lynd Ward Prize

Under the auspices of PSU Libraries and the Pennsylvania Center for the Book, I served as the chair of the selection jury for the 2013 Lynd Ward Graphic Novel Prize, “presented annually to the best graphic novel, fiction or non-fiction, published in the previous calendar year by a living U.S. or Canadian citizen or resident.”  Out of a seemingly endless pile of brilliant comics, Chris Ware’s Building Stories took home the prize.  About Building Stories, we said:

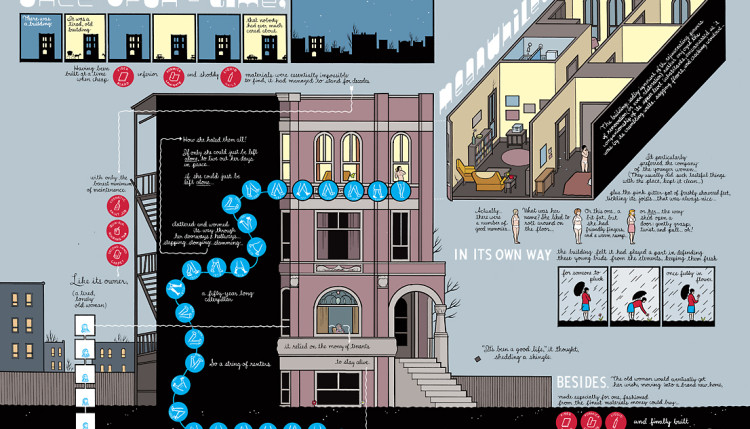

Chris Ware’s brilliant,

understated Building Stories peels back the façade of a nondescript, three-story walk-up in a tired Chicago neighborhood, exposing and empathetically deconstructing the quietly desperate lives of a thin parade of tenants who have come to call the building “home.” These lives are constellated across fourteen narrative artifacts, to be unpacked and encountered in an undetermined order, from faux newspapers and stapled minicomics to a Little Golden Book and a four-panel accordion-folded building map resembling a board game. The “building” of the title is of course both noun and verb, locale and process, stories of a building and the building of stories. But more than that, Ware’s do-it-yourself storytelling kit collapses the binary between the two: every edifice, every home, every life is an ad hoc assembly process of moments and memories, usually without much in the way of instructions. Ware’s astute and precise renderings, composed with a tender yet unblinkingly clinical eye and fleshed out with pristine and evocative coloring, trace the mundane routines and moments of small crisis that his characters inhabit. In so doing, he produces not a document but a monument, a work whose narrative logic is architectural rather than chronological: a set of lives to be encountered, traversed, and returned to as the rooms and floors of a building might be over the years, still sequentially but not in a limited or decided-upon sequence. Stories, here, are meant not to be told but to be built, explored, inhabited—not merely visited but lived in.

But for all its aesthetic precision and its formal and mediatic innovation, Building Stories is far from cold or unaffecting. Its experimental form is a mode of generosity to its characters, whose struggles with the quiet humiliations and unnoticed heartbreaks of day-to-day life take on significance not because they are the stuff of heroic epic or grand tragedy, but because in the aggregate they make up the lives of people (and of one Branford the bee) worthy of generosity, dignity, and empathy. When the narrative comforts of plot chronology and prescribed character development are stripped away, we have no choice but to engage with Ware’s characters empathetically, as individuals whose experiences matter not because they are embedded moments in a larger narrative arc but because they are moments of import to those characters. To live in these built stories is to feel deeply and generously for their inhabitants, to unpack the subtle connections between moments across a life, and to appreciate both the gentle beauty and the inestimable challenges of the mundane. The impressive power of Building Stories resides in the cooperation between its virtuoso experimental artistry and its dedicated humanism, out of which emerges one of the most accomplished, moving, compelling pieces of fiction in recent memory.

We also awarded two honor books.  About the first volume of Theo Ellsworth’s The Understanding Monster, we said:

If the crowded,

cluttered, chaotic headspace of depression and anxiety were to be mapped visually, it would probably look a lot like the labyrinthine pages of Theo Ellsworth’s The Understanding Monster. Ellsworth embraces the unenviable task of trying to capture the untranslatable, unrepresentable, illegible experience of being trapped inside one’s own head and produces out of that task an endlessly captivating and rewarding piece of visual and narrative art. His intricately drawn, richly-colored visuals sprawl across the full dimensions of each page, inviting readers into the dizzying, frantic mental space of his protagonist, Izadore—inviting in the way a maze invites entry, with a compelling sense of mystery but without any guarantee of safe exit. The narrative is equally mazelike: a robotic narrator shepherds Izadore through a dream-logic quest, a sort of in-brain heist plot in which the object is for Izadore to achieve (or re-achieve) psychological coherence and a stable identity. Along the way, Izadore is accosted by various monstrous embodiments of anxiety and self-doubt, macabre avatars of internal confusion, and psychic roadblocks that seem simultaneously cartoonish and incredibly dangerous. The book invites its readers to lose themselves in this pandemonium of the unconscious, but as the robotic narrator and other supporting characters escort Izadore through the hazards of his own brain, so do they escort us—if not to safety or ironclad emotional security, then to something approaching understanding.

About Lilli Carré’s Heads or Tails, we said:

Lilli Carré’s

masterful collection Heads or Tails is many things: a paradoxically sweet and joyous gallery of melancholic tales, a quietly sad monument to exuberance and invention, an enticing museum of visual poetry. Each story is exquisitely crafted, demonstrating both a compelling literary style and a rich, engaging design sense that can seem deceptively naïve or childlike on first glance but in context reveals striking sophistication and complexity. The tales are often bright and cheery visually, but they invariably demonstrate profound care, even affection, for the ephemeral nature of lives and longing. Carré’s precise but playful art jumps off the page, both within individual stories and in the context of the larger work, which manifests an impressive variety of aesthetics and color schemes, from the faded and monochrome to the richly prismatic. In isolation, each story is a painstakingly crafted gem, shining charismatically without necessarily yielding up its mysteries; in succession, the tales are charmingly and consistently unpredictable, resonating in unexpected ways and giving the impression of an artist who has not only mastered her craft but who maintains a constant sense of joy for that craft and for its practice from page to page. That joy is contagious, and it is what makes Heads or Tails such a wonderful enigma of a book—quite literally, full of wonders.

Update: Â it looks like the prize ceremony is up on YouTube. Â I had the considerable pleasure of introducing Chris: